Here you go! The first installment. Note that this was written to be spoken, so sometimes the diction might seem a little weird for a blog post. But I’m just going to leave it as-is, because you’ll get the idea.

Beyond Orcs and Elves: Diversity in Science Fiction and Fantasy for Young Readers

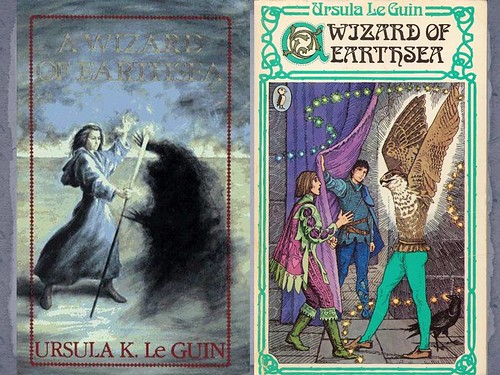

Ursula Le Guin, way back in 1975 said:

The women’s movement has made most of us conscious of the fact that SF [science fiction, but let’s include fantasy too] has either totally ignored women or presented them as squeaking dolls subject to instant rape by monsters—or old-maid scientists desexed by hypertrophy of the intellectual organs—or, at best, loyal little wives or mistresses of accomplished heroes. Male elitism has run rampant in SF. But is it only male elitism? Isn’t the “subjection of women” in SF merely a symptom of a whole which is authoritarian, power-worshiping, and intensely parochial?

The question involved here is the question of The Other—the being who is different from yourself. This being can be different from you in its sex; or in its annual income; or in its way of speaking and dressing and doing things; or in the color of its skin, or the number of its legs and heads.

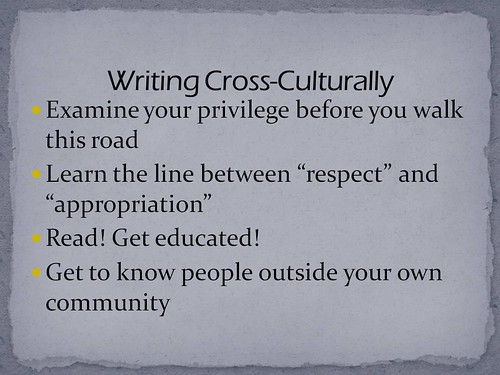

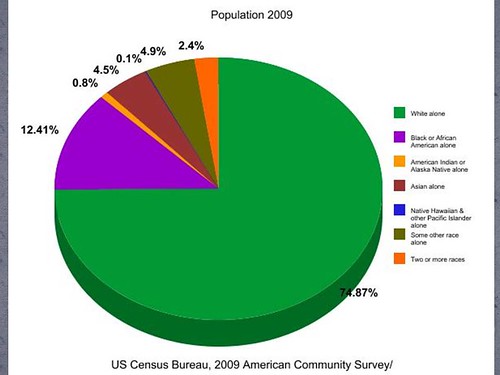

That was 35 years ago. (I know. I can’t believe it myself.) How are we doing today? I want to talk about the inclusion in speculative fiction for children and young adults of what 74% of the book-buying public might consider the Other in terms of mostly racial but also cultural differences. Perhaps this will help you in writing fantastic creatures or aliens, as well, this idea of writing the Other, but I want to focus on the human element today.

That was 35 years ago. (I know. I can’t believe it myself.) How are we doing today? I want to talk about the inclusion in speculative fiction for children and young adults of what 74% of the book-buying public might consider the Other in terms of mostly racial but also cultural differences. Perhaps this will help you in writing fantastic creatures or aliens, as well, this idea of writing the Other, but I want to focus on the human element today.

Old-school epic fantasy

- Campbellian monomyth (guys who start off their adventures in inns)

- ¨The British tradition”: Victorian fantasists to Tolkien & Lewis

- ¨My elves are better than yours”

- Dragonlance: The New Adventures

You may or may not know that fantasy as a genre started long before Tolkien was born. In fact, people have been telling fantasy stories for as long as there have been people. After all, the first fairy tales weren’t just what we now refer to as “myths,” creation stories and just-so stories. They were also fantastical tales told to pass the time or to warn children not to wander in the woods alone.

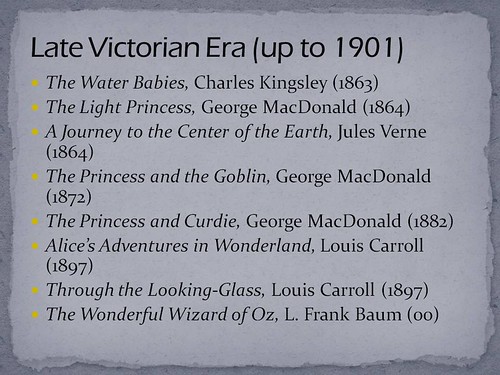

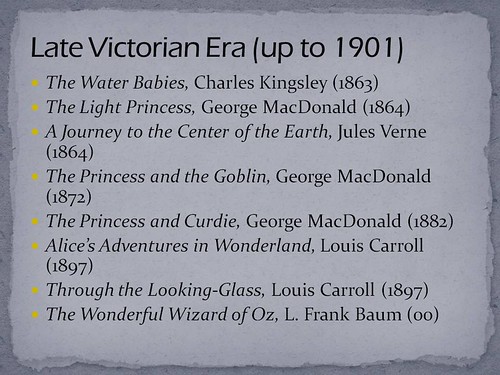

But let’s just start with the Victorian era, which had its own set of rules, morals and mores, body of literature, and cultural influences. We start with writers like George MacDonald, one of the primary influences on both Tolkien and Lewis, who wrote such tales as The Princess and the Goblin, The Light Princess, and The Princess and Curdie. His books drew upon fairy tales in their use of goblins, and they were fun, adventurous, and even allowed girls to have some adventure, which is kind of rare for the Victorian era!

There were also morality tales in the guise of fantasy—same as it ever was—such as Charles Kingsley’s The Water Babies, and the touchstone of fantasy touchstones, Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

So even back then there was a wide variety of fantastical tales for children, but as often happens, when one book gets popular, a lot of imitations abound, trying to replicate the formula for success. The “British tradition” of fantasy was born not only in the UK, but also in the US.

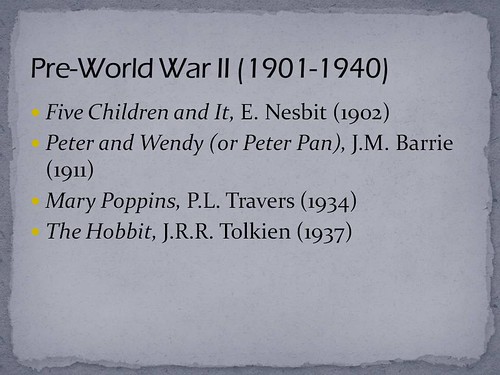

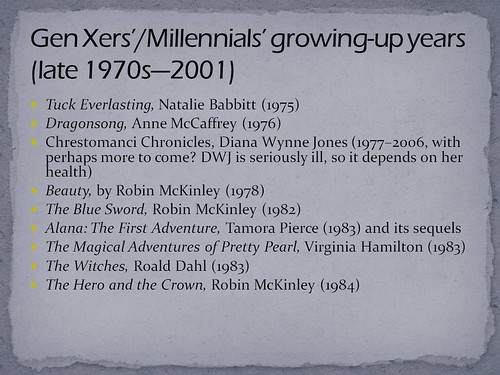

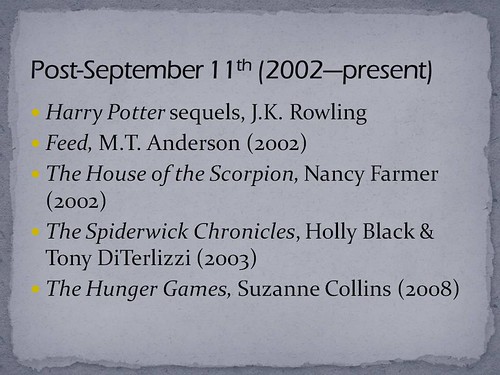

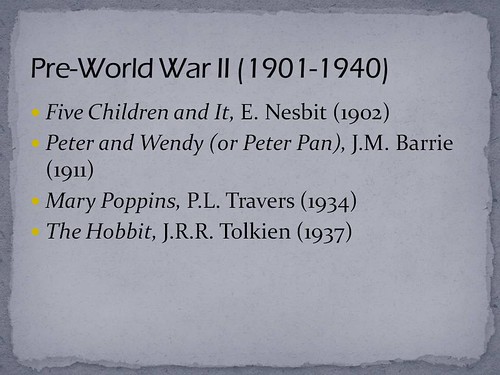

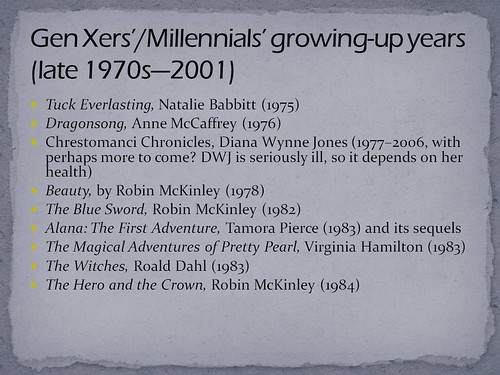

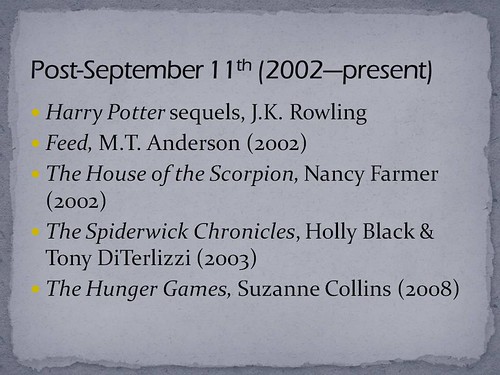

Then we move through time, hitting upon authors like

I’m just going to let those slide on by, because I want to particularly focus in on the British—particularly Tolkienesque tradition of fantasy, which is popular not only amidst adult fantasy books—the majority of readers of which is teen boys—but also some high fantasy for children. The whole list is on my blog, which is stacylwhitman.com, if you’re interested in looking it up. I just wanted to post this to give us a better idea of where we’ve come from. [NOTE: I posted these in a text version somewhere, but I’m not sure where at the moment. I’ll have to come back and edit it with a link. Or you can just go to the tags on the side of the main page and click “booklists,” which should get you there eventually.]

So, focusing in on high fantasy—books like these:

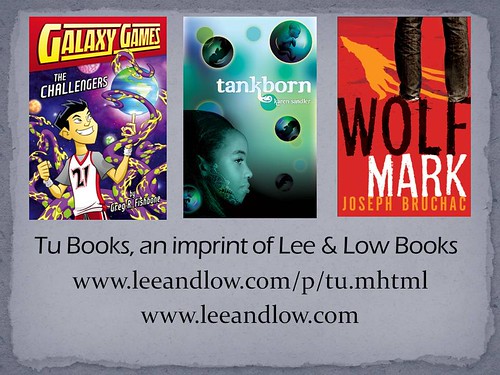

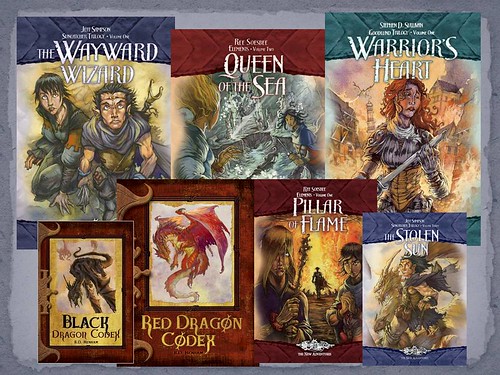

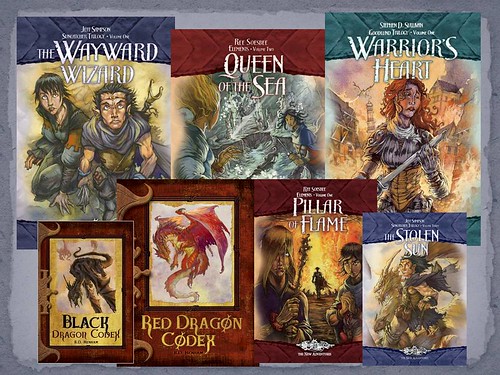

Now, these are some books I worked on. I’ll get to them in a moment. But they arose out of a long tradition of high fantasy in both children’s and adult books.

My first job as a trade children’s book editor was at Wizards of the Coast, which some of you may know is known for its Dungeons and Dragons game. Or you might know it for Magic: The Gathering. Both games have popular tie-in fiction, and that’s what I first edited at this job: Dragonlance: The New Adventures. The original Dragonlance series by Tracy Hickman and Margaret Weiss was published in the 1980s in conjunction with a D&D game by the same name, Dragonlance. The original books haven’t gone out of print in the 25 years since, and have spawned hundreds of books in the shared-world series, including the New Adventures, a series for middle grade readers that I edited.

Dragonlance was part of the larger body of epic fantasy work of the late 70s through the 80s—pre-Robert Jordan—that was eaten up by teens, mostly teenage boys (a trend that continues today). It’s great stuff! Kids and teens love it. Lots of adventure and dragons and elves and just a lot of fun.

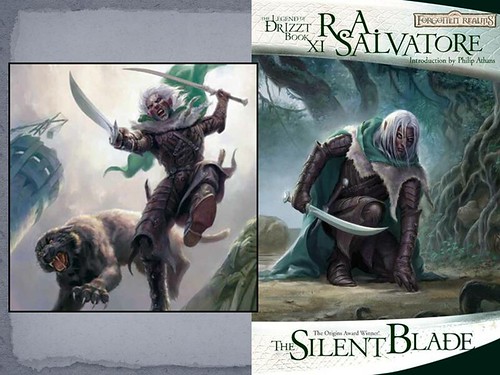

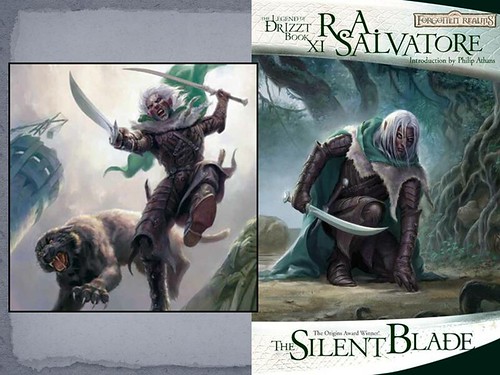

One of the hallmarks of this kind of epic fantasy are worlds populated by what has become the standard fantasy races: any combination of elves, orcs, goblins, hobbit-like halflings—called “kender” in Dragonlance, halflings elsewhere—ogres, giants, and dragons (though usually the hero is a white human or light-skinned elf or half-elf, and most often that hero is also a man/boy). I think one of the reasons Drizzt is so popular is because he breaks this stereotype, though at the same time he reinforces others (he is the only “good” Dark Elf in an entire race of people). Mind you, it makes for good game mechanics (f0r this particular game) to make it easier to play characters. But it’s when individual characters have to fit a mold racially that it becomes problematic, especially now that we’re more than 25 years on from the publication of the original books, which were groundbreaking in their own right at the time.

is so popular is because he breaks this stereotype, though at the same time he reinforces others (he is the only “good” Dark Elf in an entire race of people). Mind you, it makes for good game mechanics (f0r this particular game) to make it easier to play characters. But it’s when individual characters have to fit a mold racially that it becomes problematic, especially now that we’re more than 25 years on from the publication of the original books, which were groundbreaking in their own right at the time.

There are some major tropes in high fantasy that we see a lot especially in older epic high fantasy titles:

- Elves are beautiful, mysterious, and always good. Except dark elves, who are brooding and evil.

- Kender can’t do magic.

- Ogres are all evil. Half-ogres can sometimes be good.

- Dwarves love to mine and live underground.

- All hobbits (sometimes called halflings or kender) love to eat.

- Gnomes are all engineers who blow stuff up, sometimes killing themselves in wild ways in the process.

- Chromatic dragons are evil. Metallic dragons are good. They cannot change this fact by choosing to be good or evil, either.

Diversity issues have often been tackled in these books, though usually along strict “racial” lines which are really species lines. But each species was a kind of “people,” a sentient race of beings who could sometimes intermarry. All were humanoid. But it was a huge step in the right direction.

But how do we go beyond that?

Those involved with the adult book side of things are aware of these issues and many are working to address them in a variety of ways, but that’s not the focus of what we’re talking about here today. We’re going to talk about how it affects fantasy in children’s literature. So let’s look at a specific example. In Dragonlance: The New Adventures, we broke the mold a little bit. In original Dragonlance, the hobbit-like kender had a racial trait that they couldn’t do magic. Yes, an entire race of people, according to the rules of this world, were not genetically capable of doing magic.

Those involved with the adult book side of things are aware of these issues and many are working to address them in a variety of ways, but that’s not the focus of what we’re talking about here today. We’re going to talk about how it affects fantasy in children’s literature. So let’s look at a specific example. In Dragonlance: The New Adventures, we broke the mold a little bit. In original Dragonlance, the hobbit-like kender had a racial trait that they couldn’t do magic. Yes, an entire race of people, according to the rules of this world, were not genetically capable of doing magic.

An entire race of people were genetically incompetent in a skill which this world pretty much required for survival.

Well, not every human or elf was a magic-wielder, either, but the fact that humans and elves had the ability to choose whether or not to try to practice magic (or had the ability to find out if they were capable of it on an individual level, at least) makes it an interesting study in diversity to see that kender couldn’t do magic.

We broke that in the New Adventures, though—and some people weren’t terribly happy with us for doing it—and played with the rules of the world so that this one particular kender could do magic. There was an in-world way we explained it (he was given an older kind of dragon magic by a dragon spirit), but there you go. He wasn’t the only misfit in the group, either—the elf wasn’t all righteous and good, he was a thief. What matters is that each individual in a given group, including even minor characters, should be treated as an individual.

Part of this pattern is that much of high fantasy, at least until recent years, follows the British tradition I was just alluding to earlier—or rather, I should say, the Tolkien tradition. Tolkien did it this way and it worked so well, we should do it again and again!

Tolkien isn’t the only writer to be imitated in this way. We’ve seen it happen with every recent blockbuster, from Harry Potter to Twilight to Gossip Girls to whatever today’s new big thing is. How many boys-off-to-wizard-school books cropped up when Harry Potter first got big? But it is important to look at this tradition and realize how it’s stifled HUMAN diversity in fantasy and science fiction for young readers, and the ways in which writers are breaking that mold.

We don’t have enough time to really delve into a full analysis of each book that follows this tradition or breaks its molds, so I hope that what I say today will be just a jumping-off point for further thoughts and discussion, the end result being more writers of speculative fiction for children thinking consciously about diversity as they write.

How do we get past this old fantasy-world-trope diversity? Not in chucking elves and dragons altogether, in my opinion—it’s fun to play with made-up people and creatures!—but by examining issues of privilege and looking at how we treat individuals within groups, whether human or elf or orc. R.A. Salvatore’s Drizzt broke those old boundaries—he’s a misfit. He decided to be good among a people who are dedicated to evil. That appeals to teen readers on a number of levels, but the one that stands out to me is that the character is an individual, who goes beyond the template that drow—dark elves—are expected to have in this fantasy world.

Next time: Let’s talk about whitewashing and demographics.

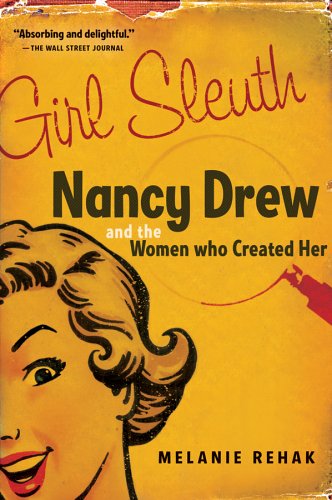

My latest read is a departure from my normal fiction fare: Girl Sleuth: Nancy Drew and the Women Who Created Her. We start off getting some biographical details of Edward Stratemeyer, who headed the Stratemeyer Syndicate—which, far from being the organized crime ring the name sounds like, was the company that created Nancy Drew back in the 20s.

My latest read is a departure from my normal fiction fare: Girl Sleuth: Nancy Drew and the Women Who Created Her. We start off getting some biographical details of Edward Stratemeyer, who headed the Stratemeyer Syndicate—which, far from being the organized crime ring the name sounds like, was the company that created Nancy Drew back in the 20s.